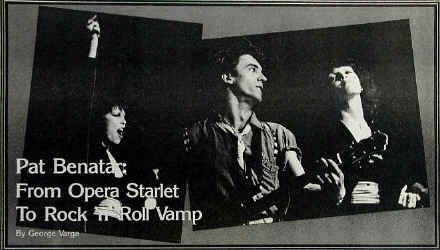

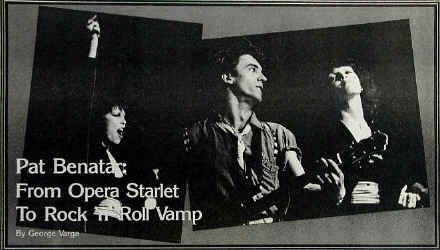

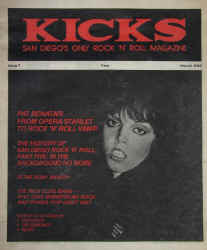

Pat Benatar: From Opera Starlet to Rock

‘n’ Roll Vamp

-George Varga

Kicks Magazine, March, 1980

Pat

Benatar is ecstatic. Her debut album, In The Heat Of

The Night, is number thirty-four with a bullet on the Billboard charts, and all available copies of the

record have sold out at the local Tower Records branch in anticipation of her Montezuma

Hall concert tonight. The show, also sold out, is the final date of a grueling

four-month tour that commenced last October.

With

the tour’s end just a few hours away, and Benatar’s single,

“Heartbreaker,” garnering massive airplay and boosting her album even higher on

the charts, it seems an opportune time to reflect on her recent success and the rigors of

headlining a national tour.

Looking

none the worse for wear and tear, Benatar appears surprisingly bright and chipper when we

meet in her Embarcadero hotel room overlooking the Star Of India. Dressed in black

designer jeans and a stylish turquoise and black boat-neck sweater, she more resembles a

vivacious college coed than the sultry, Danskin-clad siren pictured on the cover of In The Heat Of The Night.

Produced by platinum-fingered Mike Chapman

(the Knack, Blondie, Suzi Quatro), In The Heat Of

The Night is a promising, if somewhat uneven, release. The album showcases

Benatar’s soaring vocals over a backdrop of catchy power pop and ersatz heavy metal,

and although her name is not exactly a household word, Benatar has managed to attain an

unusually positive response for a new performer.

It

all seems a far cry from New York, where Benatar was born and groomed for a career in

opera by her mother. Possessing a smooth, strong soprano voice with a three-octave range,

Benatar was well suited for opera and, had it not been for a dare from a friend who

challenged her to try rock, she might to this day be performing cantatas from Carmen and assorted Wagnerian arias.

Sitting

across from Benatar in her hotel room, I find myself pondering her conversion from opera

to rock, and imagine her singing coach leaping off the Brooklyn Bridge, a broken man, following his

prize student’s defection to the vile, dreaded world of rock ‘n’ roll.

Behind us, a television flickers silently, its picture tube catching and reflecting the

gray and blue hues of the bay below. Suddenly, a booming male voice rings out across the

room.

leaping off the Brooklyn Bridge, a broken man, following his

prize student’s defection to the vile, dreaded world of rock ‘n’ roll.

Behind us, a television flickers silently, its picture tube catching and reflecting the

gray and blue hues of the bay below. Suddenly, a booming male voice rings out across the

room.

“You’ve

got great television stations here!” exclaims Benatar’s band leader and

boyfriend, Neal Geraldo. A gregarious, sincere person with a fop of wavy brown hair,

Geraldo promptly launches into a philosophical discourse concerning the moral values and

social significance of Leave It To Beaver. Benatar

smiles, then hugs Geraldo, who departs for a conversation with their manager in an

adjoining room.

With

her crystal clear operatic voice, Benatar is clearly somewhat of an anomaly in rock music,

and even at its gutsiest — as on the hit single, “Heartbreaker” — her

singing maintains an unusual degree of clarity. Was it difficult, I pose, switching

over to rock after her operatic training?

“Yeah,

opera’s a real elitist thing to do,” replies Benatar, settling her five-foot

frame on the edge of her bed, “which is why I didn’t want to do it. I was always

a maniac in my personal life and then I would have to be this other kind of thing when I

performed.”

She

perches forward, then continues. “Opera was very stifling; it was too regimented. It

was like ballet—you had to sleep, you couldn’t stay up all night and drink, you

couldn’t have any fun! You had to watch your throat constantly, which I still have to

watch anyway, but nothing like before. Rock is a much more rigorous thing, and it fits in

better with my lifestyle.

Getting

her voice to adapt to the rigors of rock was no easy matter, as Benatar candidly admits. “It was fucking hard!” she says,

laughing. “It took a good two years to change it — every night constantly

singing and listening to find out how I could scratch up my voice, rough it up, and still

not rip my throat out.” In fact,

she relates, having a classically trained voice actually proved to be a hindrance. “Oh yeah,” confides Benatar, a grin

spreading across her face, “it was a great hindrance. The technique can be applied

the same way; it’s just that the final outcome of the technique has really got to be

changed. It was really hard. There were a lot of nights when I went home crying, with a

ripped-out throat, trying to get the sound I wanted. It took a long time. It was hard to

learn not to enunciate, and it was an embarrassing time when you failed a lot, but I was

really determined.”

Benatar’s

determination and perseverance paid off, but when I venture that her success occurred

rather quickly, she tosses her head back and laughs.

“Are you kidding?” she exclaims. “It was an eight-year

overnight success. I came to New York in 1975 (following an unsuccessful marriage which

found her living in Virginia), which is when I really started singing professionally, but

before that I did lounge bands, I did Holiday Inns, I did singing waitress jobs — it

was awful!”

Following

her discovery at a New York City talent showcase called Catch A Rising Star, Benatar signed with Chrysalis

Records, which in turn led to studio wizard Mike Chapman’s agreement to produce her,

a chore he shared with fellow producer Peter Coleman. Chapman paired Benatar with Neal

Geraldo, and under the former Rick Derringer Group member’s guidance, a solid

four-piece group was formed to record Benatar’s debut album, In The Heat Of The Night. The band —

featuring Geraldo on lead guitar and keyboards, Roger Capps on bass, drummer Glen

Alexander Hamilton, and a man with the illustrious name of Scott St. Clair Sheets on

second guitar — is a solid, kinetic unit, sparked by Geraldo’s searing guitar

and a no-nonsense rhythm section. What the group lacks in eclecticism is compensated for

by its primal drive and spunk.

What prevents In The Heat Of The Night from being a total

artistic success is the material, which tends to veer too much toward insubstantial fluff,

and Chapman’s production. Although his streamlined production is reasonably engaging,

Chapman’s emphasis on attaining a slick, overly polished new wave sound sometimes

does Benatar more harm than good.

What prevents In The Heat Of The Night from being a total

artistic success is the material, which tends to veer too much toward insubstantial fluff,

and Chapman’s production. Although his streamlined production is reasonably engaging,

Chapman’s emphasis on attaining a slick, overly polished new wave sound sometimes

does Benatar more harm than good.

Still,

Chapman is in vogue at the moment, and the appearance of his name is a bonus on any album,

however objectionable his work may be to those ears not weaned on Top Forty pap. Benatar

speaks of him in glowing terms, although she doesn’t hesitate to describe him as a

“Nazi.” “You get

‘Chapmanized,” she says candidly, “but that’s why you pick him —

you want to get Chapmanized. He’s great, and working with him on the first album was

fun. He’s so good at it; you feel real comfortable. I wouldn’t have wanted to

work with anybody else my first time.”

While

Chapman’s former clients, like the Sweet, have attacked him as a ruthless dictator

unwilling to let the artist have a say, Benatar bristles at such notions. “Chapman’s real good,” states

Benatar unequivocally. “He knows what he wants, but he’s pretty good about

letting all of us contribute our own parts. He guides you — if you’re getting

astray, then he comes and puts you back where you belong. He pretty much lets you do what

you want, as long as it’s right.”

Sparked

by the success of its single, “Heartbreaker,” In The Heat Of The Night’s popularity took

many people by surprise, Benatar included. “I

actually don’t know what happened,” she admits, giggling and tucking her legs

under her. “When we did the record, everyone said not to expect too much because the

industry was in a lull. It’s real hard to say what it is about yourself that does it,

because you’re not that aware of what it is you do.”

Yet,

while she’s reticent to admit it, at least some of Benatar’s appeal stems from

her visual image as a sensual vamp, and the record company hype sheet that accompanies her

album goes to considerable extremes to reinforce that image. Replete with such

embarrassing quotes as “Most female singers say, ‘If you love me and then hurt

me, I’ll die,’ but I say, ‘If you love me and hurt me, I’ll kick your

ass,” Benatar’s biography seems to be at odds with her five-foot-tall,

ninety-five-pound physique, reinforcing the assertion that, in the male dominated world of

rock ‘n’ roll, females are often judged by appearance rather than the substance

of their talent.

There

are even those who doggedly insist that Linda Ronstadt’s mammoth popularity came

about only after her album covers started featuring cheesecake photos of Ronstadt, sans

brassiere. However debatable such statements may be, sexism is a prevailing factor in

contemporary music, and those female singers unwilling to display some cleavage or shake

their booty — Bonnie Raitt and Tracy Nelson come readily to mind —have been

unable to attain more than a cult following, however devoted.

Yet,

encountering Benatar face to face, I see no trace of a woman flaunting her sexual ware in

lieu of any musical ability. Indeed, her appearance is tastefully modest, and her manner

so unpretentious, that it’s difficult for me to reconcile her with the image foisted

by her record company. Puzzled by this seeming disparity, I ask if the image of

herself that she would like to project clashes at all with that of her record company.

“Image

is a hard thing, because they always want to put up the sexual thing,” she answers,

shifting her position on the bed and pausing for thought. “It’s like the natural

thing they want to do, and it’s O.K.,” she insists, her voice rising somewhat

defensively. “The clothes I wear at night (for concerts), I’m sure, don’t

help portray the image any other way, but that’s not the main thing. Sometimes I

would like them to forget that I’m female, and just leave it as a singer, period. But

I know that can’t happen, I know that it won’t happen, and that’s O.K. The

only thing I can do to keep it from getting out of hand is not to stress it myself. “My record company, Chrysalis, is really good

about that kind of thing; they’re not trying to do with me what they did with Debbie

Harry of Blondie. We want different things. Debbie wants to be that kind of sexual

thing.

I

ask if it’s correct to assume that she wants to be judged by her music. “Yeah, I think it’s a natural

thing,” she responds. “I grew up skinny, flat-chested, with big teeth — you

know, all the things you’re not supposed to be, and all of a sudden they propel you

into something, and that other person is like a fantasy of mine, to be her.”

As

she readily admits, Benatar’s stage outfit — black tights and hot pants —

do little to counter her image. Nor does her appearance in Creem magazine as this month’s “Creem

Dream.” Rock is, after all, a highly visual medium. Unfortunately, far too many

times, visual flash is featured to compensate for a lack of musical ability. Benatar,

ironically, has the capability of succeeding on musical terms, and it’s perplexing

that she adheres, however grudgingly, to the image depicted by her record company.

“It’s

real important to me not to be an asshole offstage,” she states flatly. “You

meet a lot of people in rock who live it like twenty-four

hours a day, and I guess that’s O.K., but not for me. I’m real family oriented

— I was a cheerleader, I was a real straight kid, so it’s hard for me to be that

(sexual image) when I’m offstage. I don’t want to come out being a tough girl,

although semi-tough is O.K.; I don’t want that sexual thing to be blown out of

proportion.”

Still,

Benatar does foster her image, at least to a degree. Her interaction with her band,

though, is overtly democratic. “We

divide it up,” relates Benatar, who has now edged to the foot of the bed. “I

give Neal the title of ‘band leader,” she continues, “but we all work as a

unit. It’s a great thing. It’s another thing they said couldn’t be done,

that they wouldn’t enjoy working under a female, but that’s not how it is.

It’s a band situation, I just front it. When we play, we’re all up-front

together; it’s not like a singer with the band back there. “It’s what! had hoped it would be. I

don’t ride in a limousine, and they don’t ride in taxis. We all go or nobody

goes. It’s a job and we have fun.”

Likewise, songwriting chores are divided up

evenly, and Benatar reveals that her songwriting inspiration can stem from just about

anything. “I have one song on the

next album,” she explains, “that’ll be called ‘Hell Is For

Children.’ I had no reason to write that song; it was from an article on child

abuse.”

As

for the cover material Benatar selects, she stresses that a song’s words are very

important to her. “I usually pick

songs for the lyrical content,” relates Benatar. “I really like to sing words. I

can’t sing a song with stupid lyrics.”

“I

like to sing aggressive songs,” she says, explaining the paucity of ballads on In The Heat Of The Night. “Even if

they’re soft, I like them to be biting, not hard, but just say something. To me to

sing a worthless lyric is like jerking the public off and jerking myself off. I don’t

get off on singing stupid lyrics. When I sing, it’s real dramatic, that’s

what’s leftover from my days in opera, so unless it puts something forward

emotionally for me, it’s worthless to sing.”

The

interview drawing to a close, band leader Geraldo re-enters the room and sits down next to

Benatar on the bed. He stares out the window, mesmerized by the calm bay.

Benatar

is asked how her mother reacted to her becoming a rock singer after all those years of

training her for a career in opera. “When I first made the transition, she was a

little freaked out,” Benatar admits, “but she likes it now; she comes to the

concerts and she really likes it. She’s the kind of mother who, as long as you

don’t kill somebody, is behind you all the way in whatever you do.” -

The

subject of her mother clearly appeals to Benatar, and she quickly warms to the topic.

“She can really tell that I like rock much better,” Benatar says of her mother,

“and she’s really behind it. My father, too. He comes. He holds his ears, but he

still comes to the shows.” She laughs. “He doesn’t understand why it has to

be so loud. (Benatar’s concert at San Diego State University is reported to be one of

the loudest in recent memory, the loudest, in fact, since English new wave group Eddie and

The Hot Rods blew out the Backdoor’s sound system two years ago.)

Our

attention is diverted by Geraldo, who draws us to the window. There he points to the stem

of the Star Of India, and at an elusive duck, which no one other than Geraldo is able to

see. Rising to leave the room, I ask Benatar one final question. Now that the

four-month tour to promote her album is just about over, what does she plan to do

tomorrow?

“We’re

going to get up, eat breakfast, and play basketball!” she whoops, her face lighting

up like a little girl’s in a candy store. “We’re going to have big fun. I

can’t wait.”

leaping off the Brooklyn Bridge, a broken man, following his

prize student’s defection to the vile, dreaded world of rock ‘n’ roll.

Behind us, a television flickers silently, its picture tube catching and reflecting the

gray and blue hues of the bay below. Suddenly, a booming male voice rings out across the

room.

leaping off the Brooklyn Bridge, a broken man, following his

prize student’s defection to the vile, dreaded world of rock ‘n’ roll.

Behind us, a television flickers silently, its picture tube catching and reflecting the

gray and blue hues of the bay below. Suddenly, a booming male voice rings out across the

room.